Your virtual reality (VR) headset powers on, and the lab dissolves into a simulated landscape.

You’re holding a golf club, and a ball sits on a putting green. The scene responds to your every step and turn.

Not since your stroke have you gripped with your left hand, but thanks to students at UBC Okanagan, VR or augmented reality (AR) could shape your recovery.

“Using AR and VR in our research allows us to create changing environments where patients can complete tasks that simulate real-world challenges, like golf,” says Celine Balay, a master’s student in psychology.

“These methods can boost traditional rehab by providing immediate feedback tailored to your needs. It also taps into the brain’s neuroplasticity—its ability to change—and may speed up recovery.”

UBC Okanagan’s commitment to interdisciplinary, experiential learning made connecting psychology and computer science possible. Pacific.

ThBalay is part of the Neuroplasticity, Imagery and Motor Behaviour Lab (NIMBL) at UBC Okanagan, where she studies brain injuries. She works alongside Ghazaleh Shahin, herself a master’s student in computer science, in the Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) Lab.

Psychology imagines while computer science adds reality.

“Celine said that just thinking about a task for five days could improve your results. I had no idea motor imagery could be that powerful. But then I started reading more about it, and the project sounded fascinating,” Shahin says.

“We’ve started by focusing on a simple task like putting a golf ball. If the feedback we provide significantly influences outcomes, the possibilities for rehabilitation are immense.”

New technology for brain injuries

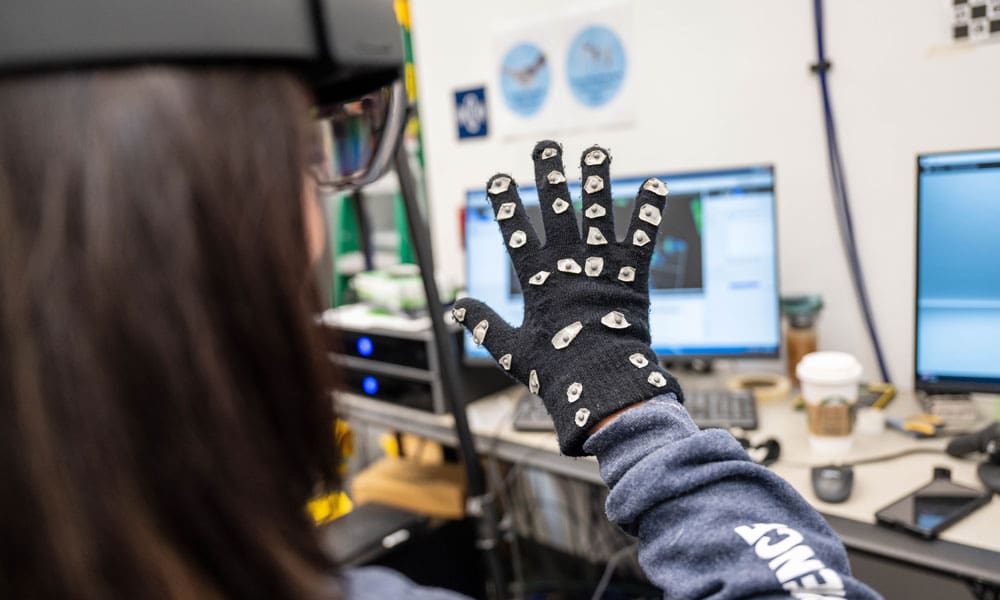

VR and AR tools like glasses, headsets and cameras can provide immediate, customized feedback by creating immersive environments to aid recovery.

Users with limited mobility can practise and visualize tasks. Their tools can simulate realistic sensory feedback that mimics physical movements, helping the brain’s ability to relearn skills after an injury.

“The research looks into an intriguing disconnect in the brain between perception and action,” says Balay. “When we practise physical movements, our hands and eyes give us sensory feedback; they shape our learning.

“Motor imagery relies purely on internal representations—what you imagine or rehearse in your mind. We’re exploring how VR could provide even greater context for anyone recovering after a stroke or brain injury.”

Advanced machine learning and data visualization refine the results. Mental imagery exercises can become even more effective by improving the strength or clarity of the images through interactive graphics and 3D views.

“By overlaying digital elements onto the real world, we can offer patients a unique, interactive experience that could significantly improve their rehabilitation,” Shahin says.

Since these initial developments, the team has been strengthened by the addition of another Master of Science student, Rishav Banerjee, who brings complementary expertise in simulation techniques.

Interdisciplinary education

A casual, on-campus meeting between computer science researcher Dr. Pourang Irani and psychology professor Dr. Sarah Kraeutner led to the partnership. They realized quickly that their students could learn from and help each other’s work.

The approach supports the idea that interdisciplinary collaboration—where researchers share unique skills and knowledge—can be more effective and responsive than working in silos or depending excessively on outside resources, says Dr. Irani, who heads the HCI lab.

“We paired these students to get our collaboration off the ground,” he says. “We’ve been discussing this for a while but find it easier when students work across the aisle rather than in isolation.

“In broad terms, Celine is the domain expert while Ghazaleh is the tech expert, and ideally, they will co-design the research experience.”

Dr. Kraeutner, Balay’s thesis supervisor and director of NIMBL, said the women have a shared vision for their work to have tangible, real-world outcomes.

“Their unique partnership bridges the disciplines of psychology, rehabilitation and computer science, creating a complementary dynamic,” Dr. Kraeutner says. “Each brings expertise from their respective fields while eagerly learning and integrating knowledge from the other domain, enhancing their combined efforts.”

Creating your education

The student researchers say they’ve come to appreciate UBC Okanagan’s willingness to let them explore outside their fields.

Shahin is researching data visualization and how artificial intelligence can create short videos that help people understand information. She wants to look for ways to blend creativity and science.

“During my undergrad in computer science, I realized I also loved graphic design and art. I was looking for a field that combined design and coding, and that’s how I found HCI,” she says.

“I’m on the computer science side, focusing on the technical implementation, but there’s room for creative problem-solving. My father is an artist who makes woodcrafts and is always looking for new ideas and possibilities. I think I inherited that from him.”

Balay is a first-generation university student who remained committed to education despite personal challenges. She’s always pursued opportunities to shape her education on her terms, including the VR-AR project.

“We’re giving patients simulated feedback during motor-imagery sessions, trying to involve the brain’s capabilities to enhance learning,” Balay says. “I’m also exploring how observing others execute a task could enhance practice. This research could unlock valuable new methods for rehabilitation and skill development.”

Stroke research obstacles

Of course, striking such a partnership presents some unique challenges. The students admit it was daunting trying to understand the intricacies of each other’s fields.

“Ghazaleh thoroughly explained the complexities of AR and VR to me. Navigating the technical aspects is daunting,” Balay says. “But collaborating with Ghazaleh helped my understanding and highlighted the immense potential of integrating these tools into the research.”

Shahin was fascinated by the initial idea, which shaped her view of the potential for good.

“As we continue to break new ground with VR and AR, the future holds such wonderful opportunities,” she says.

“Imagine a world where customized feedback accelerates recovery and transforms it. We’re not just working on recovery; we’re redefining it, making it faster, more effective and tailored to individual needs. This is more than innovation—it’s transforming how we approach physical rehabilitation.”

The article and pictures were sourced from UBC Okanagan News